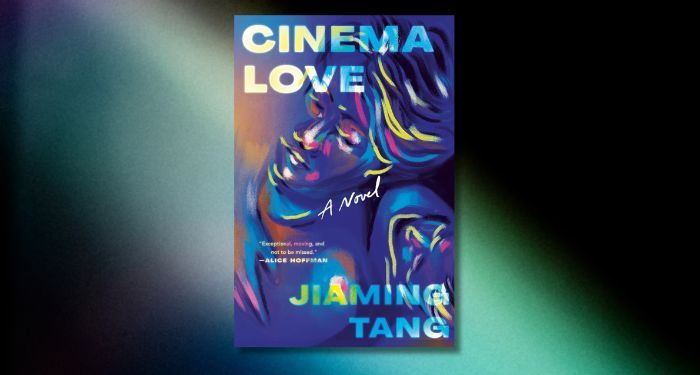

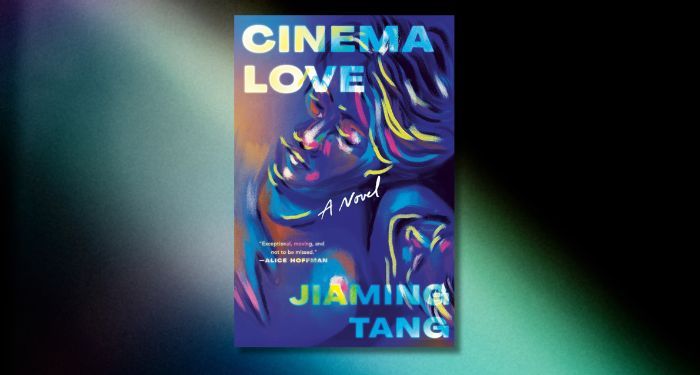

Cinema Love is a decades-spanning, multi-POV queer epic about a group of gay men and the women whose lives are tangled up with theirs. It shifts back and forth between two timelines. In rural China in the 1970s and 1980s, gay men, including a young man named Old Second, frequent a battered theatre, the Workers’ Cinema, to cruise. At the cinema, Old Second and others find companionship, love, and intimacy. For many of them, it’s the only place in their lives where they can let go of fear and be themselves. For Bao Mei, who works at the box office selling tickets, the cinema is a different kind of refuge, a place where she finds love outside the harsh societal expectations placed on women.

The second timeline, which spans the 1980s through the present day, follows Old Second and Bao Mei, now married and living in NYC’s Chinatown, having immigrated after a series of catastrophic events. They’re struggling to make ends meet in a rapidly changing neighborhood that no longer seems to care about Chinese immigrants, like them, who’ve lived there for decades. They are both haunted by their past, and despite living thousands of miles away from the Workers’ Cinema, on a different continent, it continues to define their lives and relationships in surprising ways.

This novel has everything I crave in queer fiction: a vibrant, living setting; complex and layered characters who make messy choices; rich queer history that shapes the present. It’s a book about memories and mistakes, about love and loss and how they thread through lives. It’s about how, so often, individual trauma is actually collective and systemic. Characters make catastrophic choices that do lasting harm. No one is innocent, but no one is a villain, either. It’s a book about systemic violence, about systemic homophobia and sexism and the way they insinuate themselves into ordinary lives. It’s also about redemption and forgiveness. Over decades, the characters begin to work through all the pain they’ve experienced — and caused — in a system built to kill them.

This is not an easy read, but it’s not a bleak read, either. Tang writes with such compassion and tenderness, such open curiosity about the stories behind the stories: why might someone make a choice they know will cause another person harm? Why might someone put their life on the line for a person or a place? He doesn’t answer any of these questions. Instead, through his complicated, specific characters, we get to live them.