One of the most frequent questions I get about this election is some version of, “why were the polls so wrong?”

Assessing the accuracy of polls is much more complicated than it looks.

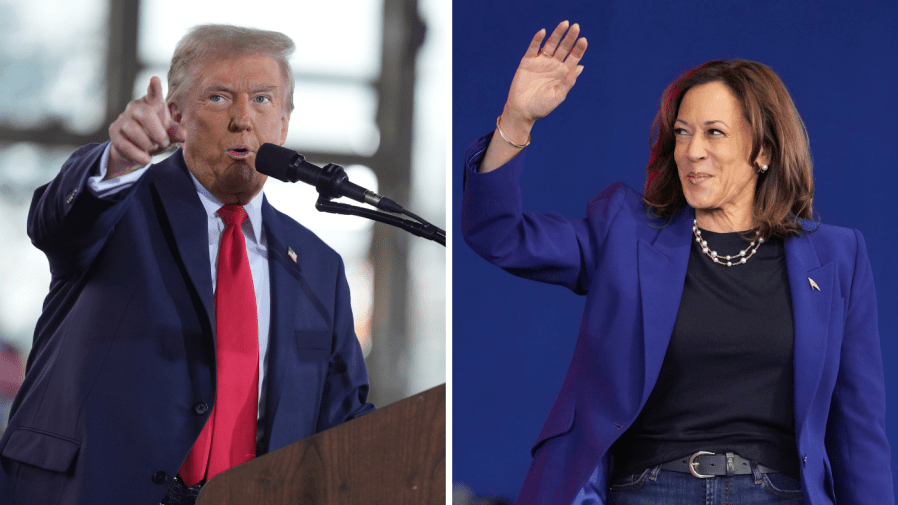

Some were clearly off. Ann Selzer is a fine pollster, but she clearly made a mistake somewhere when she found Kamala Harris ahead in Iowa by 3 points days before the vice president lost the state by 13. That’s an easy case.

There were other, less egregious, outliers, as there always are. Outliers are in consonance with the laws of statistics.

One poll had Harris 4 points ahead nationally, though she’s losing at the current count, albeit by less than 2.

A Nevada survey had Trump up 6 points, while another in the same state found Harris ahead by 3. Trump won by there by 3. Both polls were outliers; clearly neither was on target.

But which of these polls was more accurate — Echelon Insights, which gave Trump a 6-point lead in Pennsylvania, or the Washington Post poll that found Harris with a 1-point lead in the Keystone State? Echelon was “right” as to the winner, but the Post was closer to the final margin.

Academics have devised at least three rather arcane statistics to measure poll accuracy.

Just how arcane? Try to process a scholar’s explanation of one of those measures: “The A metric is calculated using the natural logarithm of the odds ratio of each poll’s outcome and the popular vote. … Accuracy can be gauged using the absolute value of the metric.”

Don’t try that yourself at home.

I’m not examining every poll here or employing every measurement method. However, I have taken a look at the relative margins in the national and swing state polls as aggregated and averaged by RealClearPolitics (RCP), which seems to massage the data less than some others.

RCP’s final poll average gave Harris a lead of .1 (that is, one-tenth of a point) nationally. Trump is now winning by 1.7 points, yielding a miss of 1.8 for the national average — pretty close, by any reckoning. And it could get even closer when the final tranche of ballots is tallied.

The biggest miss in the swing states was Arizona, where the poll average missed by 2.7. In four of the seven swing states, the difference between the average poll margin and the vote count was 1.7 points — even better than the national results.

Turn now to the seven battleground Senate contests: In three of them, the miss was less than 1 point. It averages 1.6 points. The biggest miss was in Nevada, where the polls had Jacky Rosen ahead of Sam Brown by 4.9 points in a race she won by 1.6.

The most common pushback I get to these empirical arguments is that the swing states all fell to Trump despite the close polls.

If you flipped a coin seven times, you would not expect seven heads. True. But that’s because each coin flip is an independent event. One flip has no effect on the next and no outside forces are acting on the coins to push them all toward heads.

Election results in these swing states are not independent events. The same factors that pushed Wisconsin toward Trump also pushed Pennsylvania, and even Nevada and Arizona.

Since 2004, on average, over 83 percent of the swing states fell in the same direction. Moreover, between 2004 and 2020, the press and the campaigns dubbed 11 states “swing.” This year there were only seven. Over the last 20 years, there were never fewer than seven swing states moving in the same direction.

There’s nothing odd at all — statistically or otherwise — about swing states swinging together. That’s the norm.

Critics are no doubt left unsatisfied, but there is little doubt, on average, the polls performed well this year, giving us insight into just how close this race was.

Mellman is president of The Mellman Group and has helped elect 30 U.S. senators, 12 governors and dozens of House members. Mellman served as pollster to Senate Democratic leaders for over 20 years and as president of the American Association of Political Consultants. He is a member of the Association’s Hall of Fame and president of Democratic Majority for Israel.