JMW Turner baffled his contemporaries. At the beginning of his career he was a prodigy, a preternaturally gifted tyro who joined the Royal Academy Schools at 14, and at 15 became the youngest painter ever to have a picture accepted for the RA Summer Exhibition. But at the end of his career his peers found his paintings incomprehensible. All those wafty emanations of light, colour and atmospherics had no precedent and no explanation. John Ruskin thought his late work displayed “distinctive characters in the execution, indicative of mental disease”. A fellow painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon, thought that “Turner’s pictures always look as if painted by a man who was born without hands” who had “contrived to tie a brush to the hook at the end of his wooden stump.” One critic was inspired by Turner’s ochre depictions of the ruins of Rome to brush off his Latin: the paintings, he said, were “cacatum non est pictum” – crapped not painted.

The man himself was equally mystifying. For the last five years of his life he had been living with a woman named Sophia Booth, a twice-widowed guesthouse landlady 20 years his junior. Although he had a grand albeit dusty residence-cum-gallery in Marylebone, the pair lived as man and wife – though they never married – in a house by the river (“a squalid lodging, in a squalid part of what at best is squalid Chelsea”, according to a newspaper report) and was taken for a retired seaman known as Admiral Booth: the local children called him “Puggy”.

Just as his neighbours had no idea that the squat old man dressed in black was in fact the most famous painter in England, nor did they have any idea of his means. Not only had he accrued great wealth but as well as the big house in Queen Anne Street there was also land in Dagenham and a pub, The Ship and Bladebone, in Wapping, which he would visit anonymously at weekends. At 20, he was investing money from the sale of his watercolours in Bank of England stocks and his finances were to remain a topic of intense interest to him – whether maximising his profits from prints or hard-nosed negotiations over the price of his paintings – and could go to excessive lengths. When staying with one longtime patron, Sir John Leicester, his host asked him to look over some of his own amateur efforts at painting; Turner then sent the baronet a bill for the “lesson”. A disgruntled Leicester settled the invoice but bought only one more Turner after the incident.

Here was a man who travelled everywhere with a carpet-bag he kept locked and never vouchsafed its contents; whose sketching kit included not just watercolour paints and paper but an umbrella with a dagger concealed in its handle in case of footpads; an artist who tried always to paint with the door locked and who, if observed, would cover up his picture until the prying eyes moved on; a man who numbered the pioneering scientists Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday among his friends but who failed to impress the younger French romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, who thought “he looked like an English farmer, with a black coat of coarse stuff, thick-soled shoes, and a cold, hard expression”.

This was the man whose body was retrieved by his friends from squalid Chelsea where he died in “moral degradation”, as a later account put it, and conveyed in secrecy to decent Marylebone. Turner had known he was reaching the end – a diet of milk, sherry and sucked meat proving insufficient to sustain him. When his doctor gave him his prognosis, the artist responded: “So, I am to become a nonentity, am I?” He himself, after a lifetime of unshakeable self-belief, knew this wasn’t the case and with the scandal of his living – and dying – arrangements averted, he received a funeral befitting his status at St Paul’s Cathedral. There, as he waits out eternity, this son of a Covent Garden barber and mentally unstable mother, has lofty artistic company – Sir Anthony Van Dyck, Sir Christopher Wren, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and Sir John Everett Millais among them.

What earned Turner his place among art’s knights was a career that redefined what landscape painting could do. Despite his training at the RA Schools, where antique casts and the life model were the primary teaching aids, Turner never mastered the human figure. His most concerted efforts were in a series of erotic nudes, many of which were subsequently burned by Ruskin (who, once again, thought them “assuredly” evidence of “insanity”) to preserve his reputation: the surviving sheets are not stirring. His landscapes, however, still quicken the pulse.

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Turner’s birth, an event being celebrated with a flurry of exhibitions across the country which will present the full range of his achievements in the genre: at his former house in Twickenham; at the Turner Contemporary gallery in Margate and the Whitworth in Manchester; at grand houses where he used to be a guest, such as Harewood House in Leeds and Petworth House in Sussex; and at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle, Preston Park Museum in County Durham, the Holburne Museum in Bath and at Tate Britain (paired with his contemporary John Constable).

Turner started out as a topographical draughtsman of rare refinement, able to capture in watercolour not just the detail but the evocativeness of the ruins of Tintern Abbey four years before Wordsworth complemented him in verse, or the tracery of Llandaff Cathedral and just-so-ness of Bolton Abbey sitting timelessly in its river valley. Such views were among the first of more than 37,500 works on paper he produced over the decades and were popular with collectors touched by the emerging taste for antiquarianism and a new appreciation for Britain’s ancient buildings and landscapes whetted by the continent being closed off by the Napoleonic Wars.

As early as 1791, Turner made his first out-of-London tour, visiting Bristol and the West Country, and from then on he would venture out sketching and sightseeing every year – from Wales and the Lake District to the Isle of Wight and Sussex. In 1802, with the Peace of Amiens bringing a temporary halt to the war with the French, he journeyed to Paris and Switzerland. In 1819 he added Italy and everything it meant artistically and historically to his list, taking in Venice, Rome, Naples, Paestum and Florence.

Such first-hand experience was vital to his development. Turner was born at a time when theories about landscape, and the distinction between the beautiful, the picturesque and the sublime in nature, had been given prominence by the likes of Edmund Burke and William Gilpin. On his travels he saw the categories reflected in real vistas and in all weathers. As he put it: “There’s a sketch at every turn.”

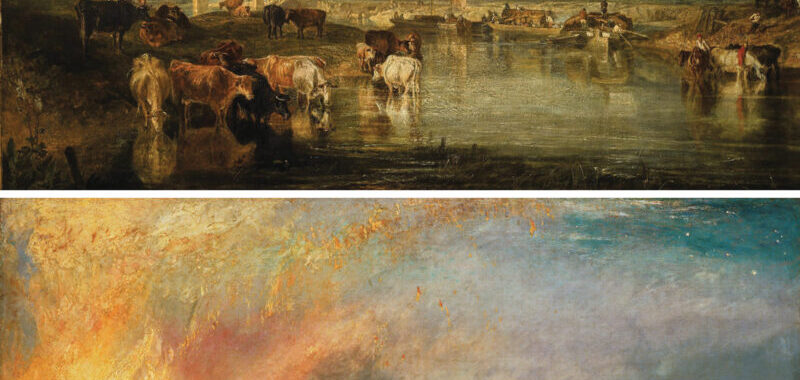

However, his most profound engagement with the landscape came through art. When he saw two paintings by the 17th-century classicist Claude Lorrain in the collection of the financier John Julius Angerstein, he was shaken. According to a witness, on encountering Claude’s Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, “Turner was awkward, agitated and burst into tears.” And from that moment on he considered Claude’s “amber-coloured ether” and paintings humming with “every hue and tone of summer’s evident heat, rich, harmonious, true and clear” to be the highpoint of landscape art. When he wanted to imbue his own pictures with the “grand manner” of history paintings, he adopted the Frenchman’s high viewpoint with framing trees, his softening middle grounds with water (water features in fully half of Turner’s pictures), and his hazy, mountainous horizons. Claude painted the Roman Campagna, Turner shone that rich and warm light on Wales, Yorkshire and the Thames Valley.

The strength of the affinity felt by him for both Claude and for landscape as an elevated subject was made clear in 1829 when he made his first will. In it he provided for a Chair of Landscape at the Royal Academy and a gold Turner Medal for landscape painting; instructed almshouses to be built for “decayed English artists and single men” as long as they were landscapists, and left a large bequest of his paintings to the National Gallery with the stipulation that two of them, Dido Building Carthage and Sun Rising Through Vapour, should be hung alongside a pair of Claudes, Landscape With the Marriage of Isaac and Rebecca and Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba.

It was Claude’s “ether” that lay behind his later experiments in atmospheric landscape where his earlier fidelity to observed nature turned into something more experimental: “It is necessary to mark the greater from the lesser truth,” he said, “namely the larger and more liberal idea of nature from the comparatively narrow and confined; namely that which addresses itself to the imagination from that which is solely addressed to the eye.”

Not that the two were separate. The story behind his Snow Storm (1842) – that he was tied to the mast of a steamship to observe a blizzard at sea – is almost certainly apocryphal but he did have himself rowed to the centre of the Thames to make documentary sketches of pyromaniacal excitement as the Houses of Parliament were consumed by flames in 1834. There is a ring of truth too to the tale of Turner in 1810 standing in the doorway of his friend Walter Fawkes’s house in Yorkshire and jotting on the back of a letter visual impressions of a storm barrelling down the valley. He told Fawkes’s son, who was watching him, that he would see the same storm again in two years, this time in a painting. Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, with its swirling vortex of stygian cloud, was first exhibited in 1812 and remains one of his most celebrated works.

The mature Turner was never a painter of line but always one of mass, tone and light. For him the four elements were interchangeable; he treated land as if it were air and air as if it were water. “Indistinctness is my forte”, Turner acknowledged, but he used that indistinctness to express his pantheistic stirrings. The mists and vapours, deliquescing views and washes of colour that took his paintings to the edge of abstraction and so appalled his contemporaries are not just emotions but expressions of the numinous. After all, as he famously said, “The sun is God.”

The potency and resonance of these pictures was not recognised fully for a century after his death. Kenneth Clark recalled seeing rolls of these canvases piled up in the cellars of the National Gallery in the 1940s where they were mistaken for old tarpaulins, and even glimpsing a watercolour sheet used to patch a broken window. It wasn’t until the decades of abstract expressionism and Mark Rothko that Turner was hailed not just as a proto-impressionist but a colour field painter avant la lettre.

Turner had earned his late style, the technical brilliance of his first four decades freed him to pursue art of increasing experimentation. He claimed to be always driven by some “fresh follery” but it was “follery” that led to paintings of extraordinary profundity.

[See also: Joan Didion without her style]

Content from our partners