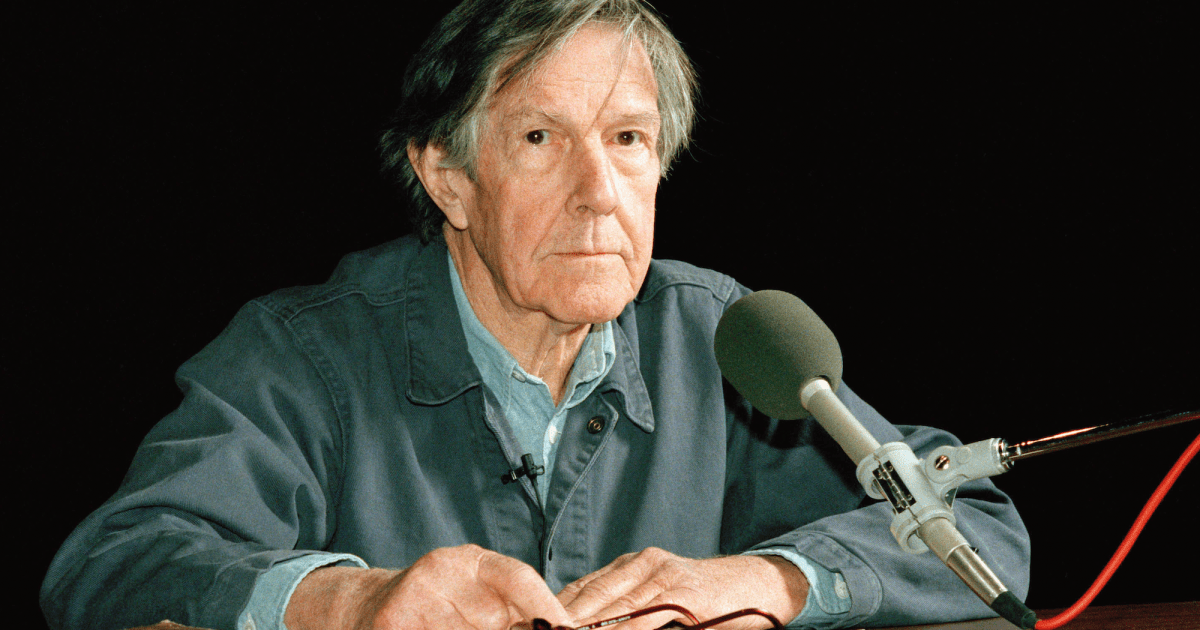

Julia Malakie/AP

John Cage, the influential composer and artist, is dead. So it’s technically impossible to know with absolute certainty how he would feel about the pro-Palestinian encampment at Columbia University.

But the question emerges after New York Times columnist John McWhorter, a music humanities and linguistics professor at Columbia, wrote that he was forced to stop students from playing Cage’s 4’33”—a seminal work that’s effectively four minutes and 33 seconds of silence (though Cage-heads might disagree with that description)—because of the demonstrations. According to McWhorter, that silence, which would have made room for the chants outside, would have inflicted cruelty on his students, some of whom he identified as Israeli and Jewish American.

But for people familiar with Cage’s work, McWhorter’s argument appeared antithetical to the spirit of 4’33”. Cage’s conception of silence, though heavily and often debated, went beyond the idea of serene nothingness. See, for example, his explanation of listening to traffic:

To see how Cage would have felt about his name being invoked in a piece that essentially browbeats antiwar protests, I reached out to Professor Philip Gentry, a musicologist at the University of Delaware who wrote a book on Cold War politics and American music that touches on Cage’s politics. His response, which has been lightly edited for clarity:

Ironically, Cage once attended lectures at Columbia University, with the Zen Buddhist scholar Daisetz Suzuki. He frequently told a story of how Suzuki would leave the classroom windows open in nice weather, and the sounds of planes flying into LaGuardia would drown out the lecturer’s voice—but there was a lesson to be learned in that.

The idea of 4’33” is to provide a frame for listening to the sounds of the world as a piece of music. Sometimes this means the sounds of nature, but most often it is the sounds of people. At the premiere in 1952 in Woodstock, NY, the initial sounds were of the forest surrounding the concert hall. By the end of the four and a half minutes, however, those natural sounds were drowned out by audience members who began to complain. Supposedly, one person stood up to shout, “Good people of Woodstock, let’s run these people out of town!” Cage was thrilled.

I suspect John Cage would have been equally pleased to know that a performance of 4’33” at Columbia in 2024 could contain, in addition to the sounds of the HVAC system and students breathing and shuffling their feet, the chaotic noise of the encampment outside the window. Whether or not he would have agreed with the protestors—he was a life-long anarchist who tended to sniff at student protests—he absolutely would have embraced that wide world of sounds. And while I can’t speak for them, it sounds like McWhorter’s students might have been subtly encouraging him to open his ears up a little wider as well.