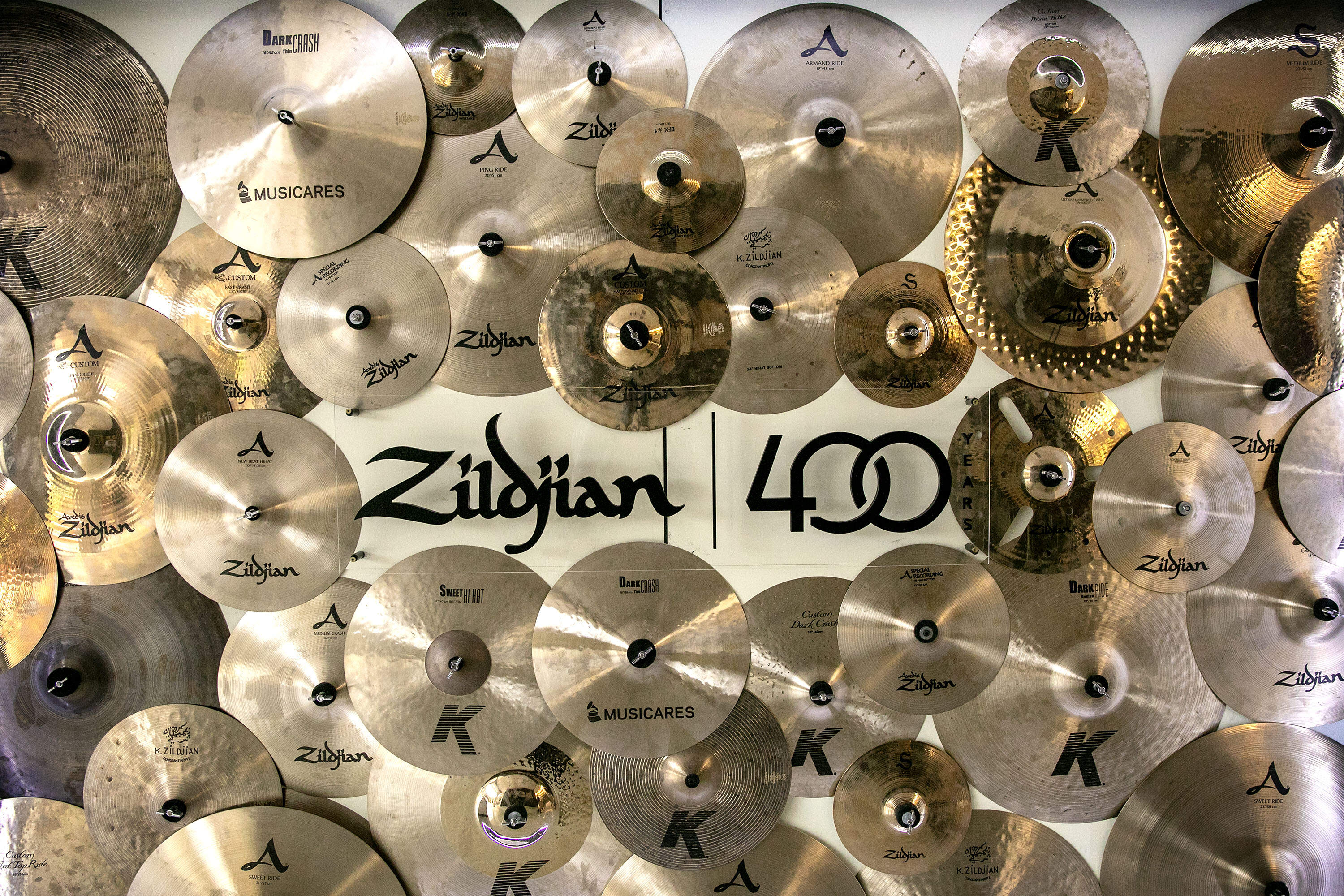

From symphonies to rock music, marching bands and advertising jingles — we hear Zildjian cymbals everywhere. Drummers across the globe know that name because it’s emblazoned on every gleaming disc. What’s less known is the Zildjian family has been making their famous cymbals — with a secret process — for more than 400 years.

Since the 1970s, the Avedis Zildjian Co. has operated under the radar in Norwell, Massachusetts. We jumped at the chance to get inside the world’s oldest cymbal manufacturer.

Even in Massachusetts many people have no idea an industrial factory outside of Boston designs, casts, blasts, rolls, hammers, buffs and tests at least a million Zildjian cymbals each year.

“There’s a lot of mystique and a lot of history at this facility,” said Joe Mitchell, the company’s director of operations, as we walked past loud, hulking machinery. He’s one of the few privy to a Zildjian process that’s been shrouded in mystery since the height of the Ottoman Empire. It begins in a room that’s off-limits to the public.

“Behind this door is where we have our foundry,” Mitchell explained. “This is where we melt our metal and where we pour our castings. I’ll show you what the castings look like — but obviously we can’t go beyond this point.”

He leaned over a bin filled with chunky, rough-hewn metal discs. Even in their nascent state, Mitchell said the castings possess the secret to Zildjian’s sound. He struck one lightly to release an enchanting, reverberant ring.

The company’s proprietary alloy was alchemized 13 generations ago in Constantinople (now Istanbul) by Debbie Zildjian’s ancestor, Avedis I. He was trying to make gold, she said, but he ended up concocting a combination of copper and tin. “The mixing of those metals produced a very loud, resonant, beautiful sound,” she said.

Debbie explained that in 1618 the Ottoman sultan summoned Avedis to the Topkapi Palace to make cymbals for elite military bands. The metalsmith’s work pleased the ruler, who gave him permission to found his own business in 1623. The sultan also bestowed Avedis the family name “Zildjian” which actually means cymbal maker. He went on to craft cymbals that were widely used, including in churches and by belly dancers.

By the 1700s European composers, including Mozart and Haydn, added Zildjian cymbals to their symphonies. “So, that’s how the reputation grew,” Debbie said.

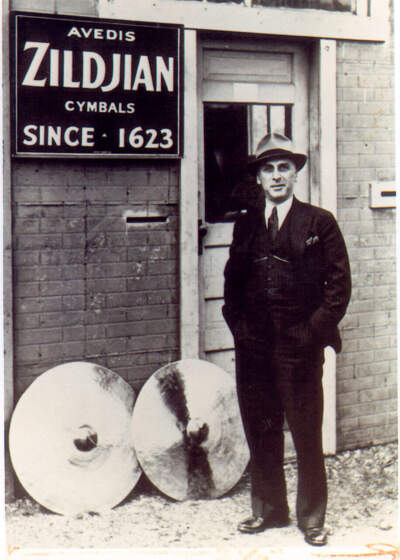

Zildjian became synonymous with cymbals after her grandfather Avedis III, an ethnic Armenian, emigrated to the U.S. in 1909. Two decades later he re-located the family’s cymbal business from Turkey to Quincy, Massachusetts with his uncle.

At the time jazz was exploding, so Avedis III travelled to New York City so he could develop new sounds with pioneers, including Gene Krupa. “Not only was he a fabulous drummer,” Debbie said, “he was also very flamboyant in his style.” This made Krupa an ideal ambassador for Zildjian.

The company really took off with a little help from The Beatles’ 1964 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. “Everybody wanted to become a musician,” Debbie said, “and it was in a matter of months that we were totally backordered because Ringo was a huge celebrity. So that catapulted our business into the modern era.”

In 1973, Zildjian moved to a state-of-the-art factory in Norwell. Debbie said her father Armand, who was then running the company, loved music like his own father. “What my father really understood — and kind of preached to all of us here — was we have to follow the music,” she said.

Armand, who started working in Zildjian’s melt room when he was 14, eventually brought Debbie and her sister Craigie inside to teach them the secret process. The family business had always been passed down to the eldest male, but Debbie and Craigie were their father’s heirs.

“For us, it was very natural on the inside, but the music industry had a hard time accepting women in the business,” Debbie said. “The players were all men, manufacturing was done mostly by men, the salespeople were all men.”

Craigie became CEO in 1999. Now she’s president and executive chair of the board of trustees. Debbie gravitated to manufacturing and oversees Zildjian’s proprietary alloy process taught to her by her father.

Over the decades, drummers across all genres have embraced Zildjian cymbals – from Lars Ulrich of Metallica to Grammy Award-winning jazz drummer Terri Lyne Carrington.

“I normally play about six cymbals plus hi-hats,” she said, “They are the sound I’ve been playing my whole life because most jazz drummers play Zildjian cymbals.”

Carrington founded and directs Berklee College of Music’s Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice in Boston. She’s also a Zildjian artist, which means she exclusively endorses and plays the company’s cymbals. Carrington said they’ve helped forge her musical identity since she was 10 years old.

“Your cymbals are your signature,” she explained. “So whenever you play, you’re generally recognized by your cymbal sound, and your touch, and your cymbal patterns — at least in jazz.”

Carrington’s drum kit is like a painter’s palette. The sound of each cymbal guides her to the next stroke. She’s visited the Zildjian factory many times and still marvels at what they do. “I don’t know the secret sauce,” she said, “but to make a piece of metal sound so pretty — and become this beautiful instrument that’s a part of every kind of music that you hear — is pretty remarkable.”

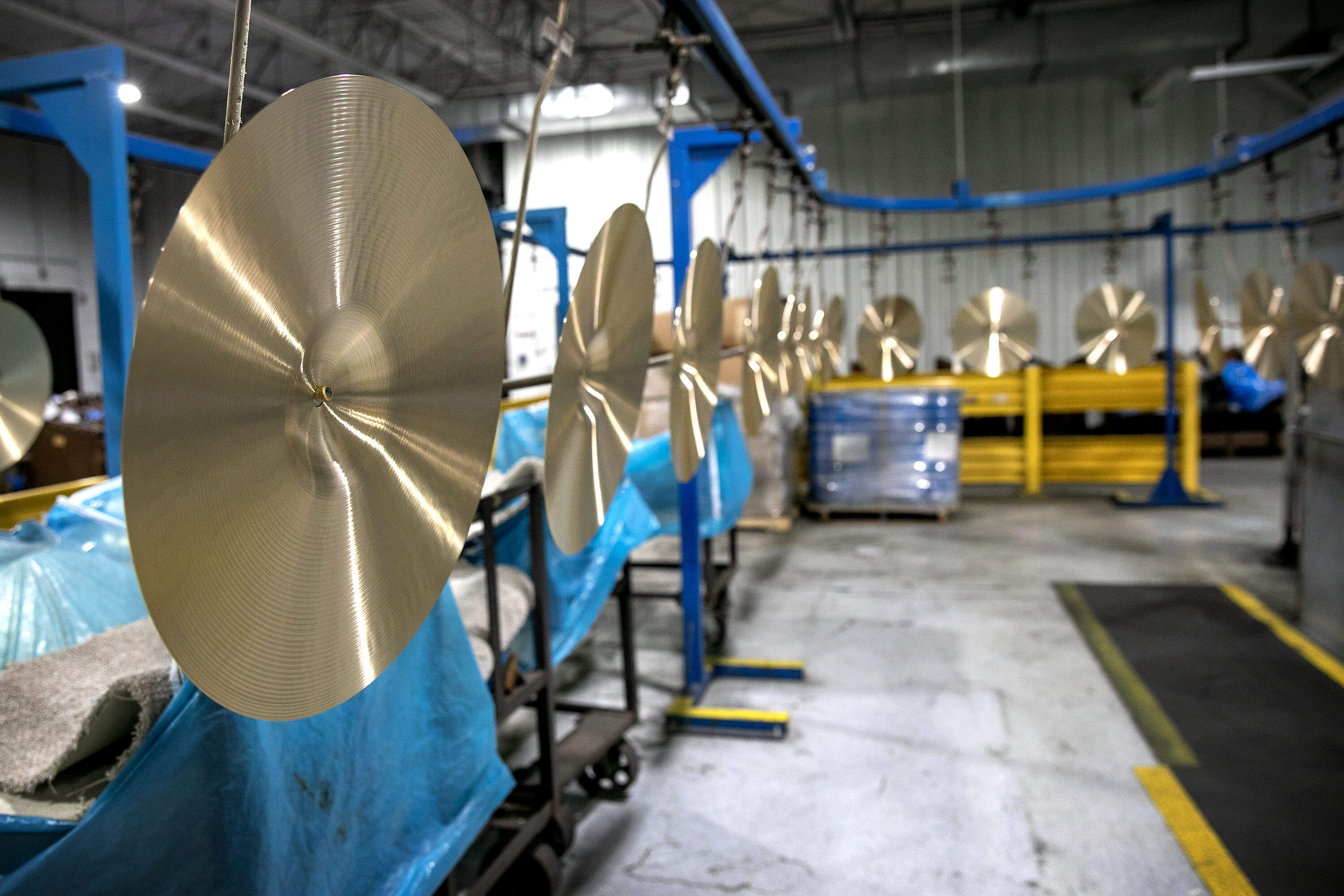

Zildjian’s manufacturing has evolved to keep up with demand for its 600 models of cymbals sold in more than 100 countries. According to the company, it takes a minimum of 15 people to complete a single cymbal. Today machines hammer the alloy instruments, but their forms are still finessed by skilled craftsmen.

Before each cymbal is deemed worthy for artists or retail it has to pass a human ear test. That’s Eric Duncan’s job. “This is the make or break point,” he said in the testing room.

One after another, Duncan lifted cymbals from a rack to compare their sound with a pristine example. “We test anywhere from 1000 to 4,000 cymbals a day, depending on how busy we are.”

Each approved cymbal gets stamped with the family name. They call it the “Zildjian kiss.”

While so much of the cymbal-making process hasn’t changed since the 1600s, Debbie Zildjian said expansion and innovation have been critical for the company’s longevity. She pointed to merging with the drumstick company Vic Firth in 2010 and this year’s debut of Zildjian’s first electronic drum kit.

“We will never abandon the acoustic,” Debbie said, “but electronic is the wave of the future.”

Debbie loves sharing her family’s storied past, but, as a keeper of their closely-guarded 400 year old alloy she doubled down, “The secret part will remain a secret.”